Medscape recently revived an old, but always somewhat contentious, question: should oncologists use the word ‘cure’? Excerpt:

Even in the best-case scenarios, oncologists may dodge the word cure, searching for others such as “remission,” “no evidence of disease,” and “most likely cured” to communicate the good news. Using these more open-ended terms can give patients reassurance without providing false hope that the cancer won’t ever return.

Reader comments included these:

Medscape’s story links take you to two articles from about five years ago in the same journal - JNCI Cancer Spectrum. One was a study, Oncologists’ Reluctance to Use the Terms Hope and Cure; the other, an editorial, “When Should Oncologists Use the Words Hope and Cure?”

The study - of thousands of articles in two major cancer journals over 20 years - showed that the words hope and cure were used infrequently.

The editorial points out, though, that:

It is necessary to distinguish how oncologists communicate in journal articles vs. how they communicate to patients. Journal articles typically describe groups of people, and the terminology and syntax are aimed at a target audience of other oncologists. Given neither hope nor cure has an accepted definition in oncology, it is not surprising these words are seldom used in publications. When oncologists communicate with patients, the audience is an individual with cancer and the language used needs to be clear, easy to understand, and reassuring.

It notes, further, that results of a survey of 117 American oncologists published 12 years ago showed that:

81% responded that they were “hesitant to tell a patient that they are cured,” and 63% responded that they “would never tell a patient that they are cured.” Only 36% of respondents were “comfortable telling a patient that they are cured within 0-5 years after completing the initial phase of their treatment,” with most respondents wanting 6-10 years or longer before using the word cured.

The study, editorial and survey mentioned above are all available, in full, online, so you can access them and read for more details.

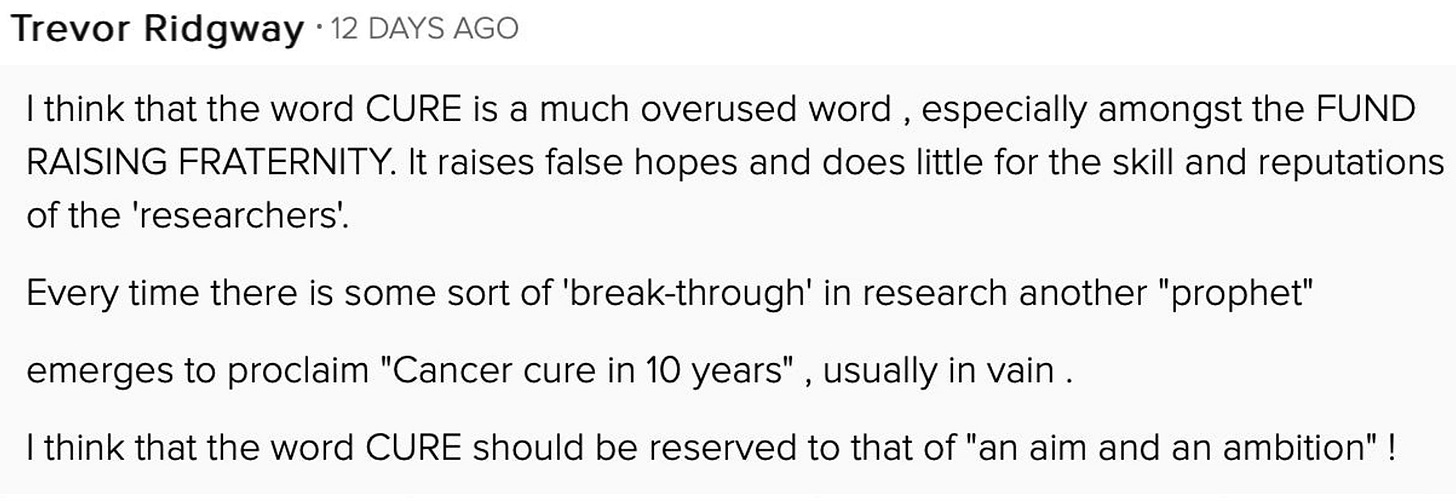

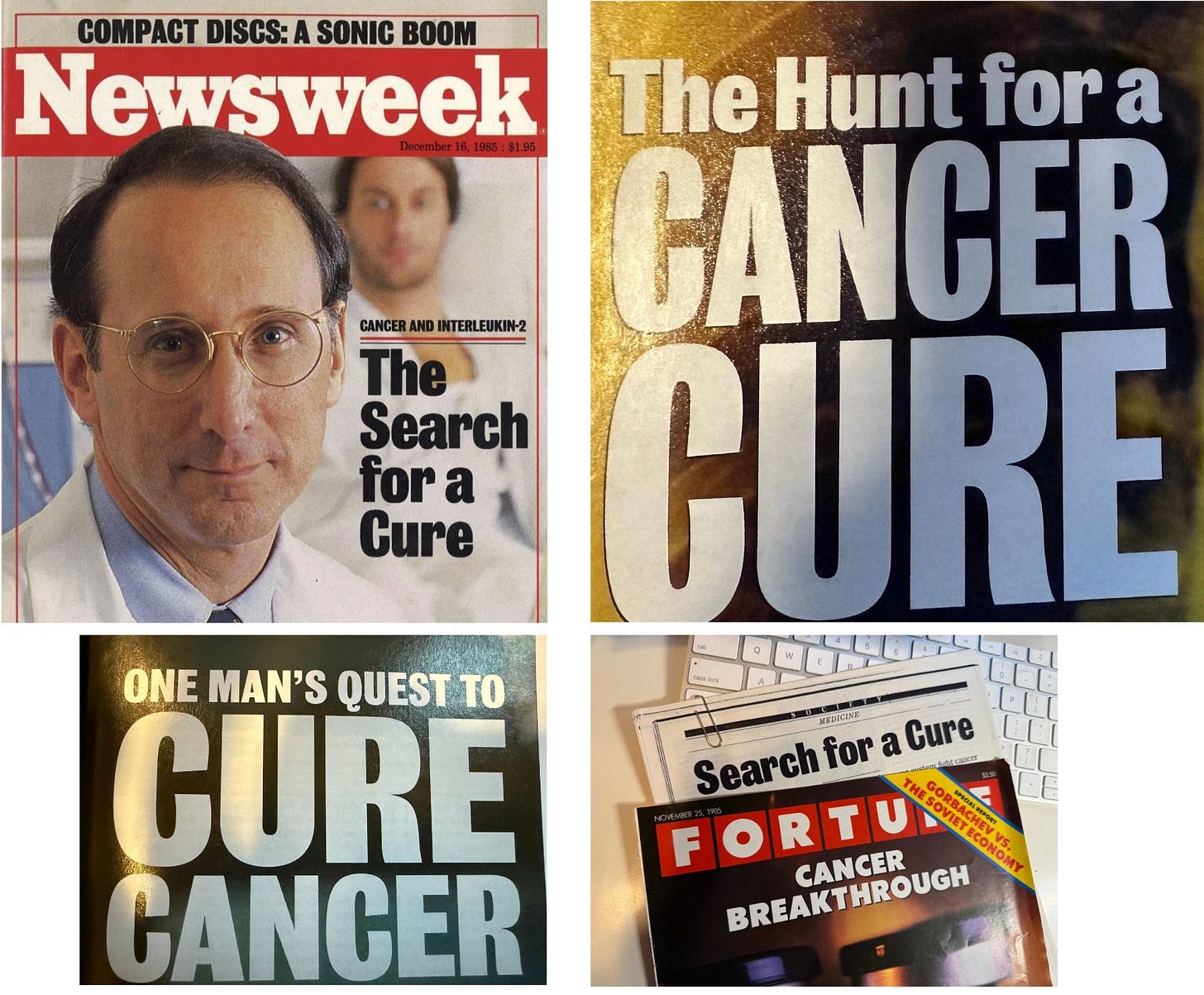

As a health care journalist for 50 years, I have saved a lot of “cure” cover stories and headlines that bothered me. The ones above are all from the 1980s, I believe. I’ve often criticized the use of both cure and hope when I felt it was unwarranted. A quarter-century ago (!), I published a piece while at the Mayo Clinic - “The 7 Words You Shouldn’t Use in Medical News.” That hyperlink takes you to an updated and revised list that I published years later on my HealthNewsReview website. Two of the seven words were cure and hope - with the following explanations:

Cure always has been one of the most loaded and ill-defined terms used in medicine or by the people who cover medicine as journalists. Does it mean absence of disease? Does it mean no recurrence of once-existing disease? Does it mean today, next week, 5 years, or a “normal life expectancy”? Does it mean the same thing to doctors as it does to those they treat? The term can be as meaningless as “expert,” which has been defined as anyone talking about anything more than 25 miles away from home.

Veteran science writer Victor Cohn once chided medicine and the media by saying, “It seems like there’s only two types of medical news stories: new hope and no hope.” A woman struggling with cancer once told me she wished medical reporters would leave the word hope out of their stories and allow patients to decide how much “hope” to assign to each story.

The volume of stories that claimed that something either killed people or cured people became fodder for a British website (no longer active) that had this banner:

Marketing messages from advocacy groups, medical centers and nonprofit health organizations also have a history of liberal use of cure.

My all-time favorite cure quote is from urologist Willet Whitmore, MD, who was chair of urology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York for 30 years. He was called “the dean of urologic oncology…possibly the greatest urologic cancer surgeon of his generation.” I’ve seen various versions of this quote about treatment for prostate cancer, but this is the one I’ll go with:

“Is cure necessary in those for whom it is possible, and is cure possible in those for whom it is necessary?”

Clearly, the definition of cure is unclear. Anyone who uses it should be aware of the confusion, the impact of the word on different audiences, and the fact that better words probably apply in most circumstances. It’s one way to avoid avoidable harm.

Addendum: Howard Wolinsky, on his excellent “The Active Surveillor” site, recently posted on a related topic: “The ‘anxiety bomb’—CANCER!—and how some doctors are trying to remove the ‘C word’ from GG1 & Ductal carcinoma in situ.”

A wonderful review of decades of news reports. And, we're still no better, I'd say at reporting on medical research and studies. Haven't there always been "miraculous" outcomes. I have a friend who had a dire diagnosis years ago and is alive and well today. Just as I've had many, including my father who died in 1980 after getting a diagnosis earlier of lymphoma and was told it was one of the better cancers to have. Perhaps people should recognize that there are just too many variables to apply to an individual. It's always been a problem to translate "population" outcomes to an individual.

This has inspired me to write on this. So many important nuances that need to honestly and openly discussed. Naming my Substack “Curative” was by intention and I think there as I think so much misunderstanding around the word.