When the FDA recently approved the Lumipulse blood test to help diagnose Alzheimer’s Disease, there was the usual roundup of hyperbole which can be harmful to public understanding. This may be an important biotechnological advance. But it’s essential for journalists to explain the limitations, the cautions, and what the test was specifically approved for.

CBS Mornings Plus co-anchor Tony Dokoupil led into this story with these comments:

“By the way I have a more than healthy fear of dementia, and so I’m excited about this health news….a disease that I and many others fear…Adriana (his co-anchor) also has a fear of dementia.”

So he squeezed in three mentions in a short segment about how both anchors in their early 40s fear dementia. Later in this article you’ll see an expert’s comments on instilling unnecessary fear in people who are simply having “senior moments” - not to mention 40-year olds. Add this story to my long list of examples in which journalists inject themselves into health care stories in ways that, in my opinion, are inappropriate. Allow the data on the test to stand on their own merits. Viewers don’t need to hear about your fears to get them interested in what’s to come.

I will say that CBS medical news contributor Dr. Celine Gounder did a reasonably good job providing appropriate context and caveats for the test.

FoxNews.com used this headline:

7 million Americans with the common dementia could benefit from less invasive diagnostic, experts say

That’s actually not what experts said. An FDA news release announcing the test approval stated: “Nearly 7 million Americans are living with Alzheimer's disease.” Fox News said 7 million “could benefit.” That’s using the statistic in the wrong context. The story also failed to mention a key phrase from the FDA release, that: “the test is intended for patients presenting at a specialized care setting with signs and symptoms of cognitive decline.”

VeryWellHealth.com used a headline that makes my skin crawl:

It may be simple to do the blood draw, but any test that can produce false positives or negative findings concerning Alzheimer’s disease and that is intended for use only in a specialized care setting is not so simple. It is NOT a screening test for the general population, which is what that headline could suggest to many readers. This theme about the test’s simplicity was fueled by an often-used quote that you’ll see below.

MedPageToday.com put limitations in its sub-headline, which was good…

…but they let Howard Fillit, MD, chief science officer of the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation get away with saying:

"The ability to diagnose Alzheimer's earlier with a simple blood test -- like we do for cholesterol -- is a game-changer.”

That statement needed to be challenged. This new test - for a highly specific target audience and with the caveats that it be interpreted in conjunction with other patient clinical information - is not at all comparable to a cholesterol test to screen the general population. This is a misleading statement that gives the wrong impression to anyone who reads it. Again, the new Alzheimer’s test is NOT a screening test. That same quote was used - without challenge to the validity of its comparison - by CNN, USA Today, US News & World Report, HealthDay, and others.

The Washington Post also had one important angle but one glaring weakness in its story.

When quoting Howard Fillit, MD, of the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, who called this “an incredible advance,” it disclosed that Fillit’s foundation “financially supported” the development of the test. In his foundation’s news release, Fillit was quoted: “We’re proud to have played a role in advancing this achievement.” So his perspective is inherently biased - worth mentioning - but the Post’s was the only news story I saw that mentioned this. So that was well done.

But here’s what wasn’t well done. Recall that when the FDA announced approval of the test, it stated: “The test is intended for patients presenting at a specialized care setting with signs and symptoms of cognitive decline.” But The Post paraphrased Dr. Fillit saying, “Patients who are experiencing memory problems generally begin by seeing a primary care physician, he said. Now those doctors could order a blood test and, if positive, refer a patient to a neurologist.” If a primary care physician orders the new test, that is not the “specialized setting” in which the FDA intended the test to be used. The Post should have caught that and commented on it. (The importance of this distinction is discussed further two items below.)

WHYY, the public media organization in the Philadelphia area, put caution in its headline. That’s not done often enough so I applaud what they did.

The strongest challenge that I found to the enthusiastic news coverage came from an op-ed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette by Georgetown professor Adriane Fugh-Berman, MD, and senior research fellow Judy Butler at the PharmedOut project that Fugh-Berman leads.

Excerpts:

“…approval of the first blood test to aid in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease sounds like a good thing for patients, but it’s not. …

Drug companies want the test to be used for screening by primary care doctors to triage patients and refer anyone with a positive blood test to a neurologist, but that’s backwards. Only someone with cognitive deficits inconsistent with age should consider an Alzheimer’s blood test, and only in a specialized care setting. Nonetheless, pushing “early diagnosis” in primary care offices is a key marketing strategy.

…Instilling insecurity and fear in people who experience “senior moments” is another marketing strategy. On Lilly’s “More than Normal Aging” website, the company encourages anyone with misplaced keys or forgotten groceries to act now, listing a blood test as the first evaluation that should be done.

Marketing this test as a screening test is not what the FDA approved it for, but drug companies are not the only entities that are promoting — and benefiting from — these tests. UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, a patient advocacy group receiving support from Biogen, celebrated FDA clearance as a way to bring the blood test “into everyday medical care.”

…The consequences of misdiagnosing Alzheimer’s are serious, especially when prescribing new, dangerous treatments. The new blood test may be a technological breakthrough, but it’s not the answer to preventing Alzheimer’s.”

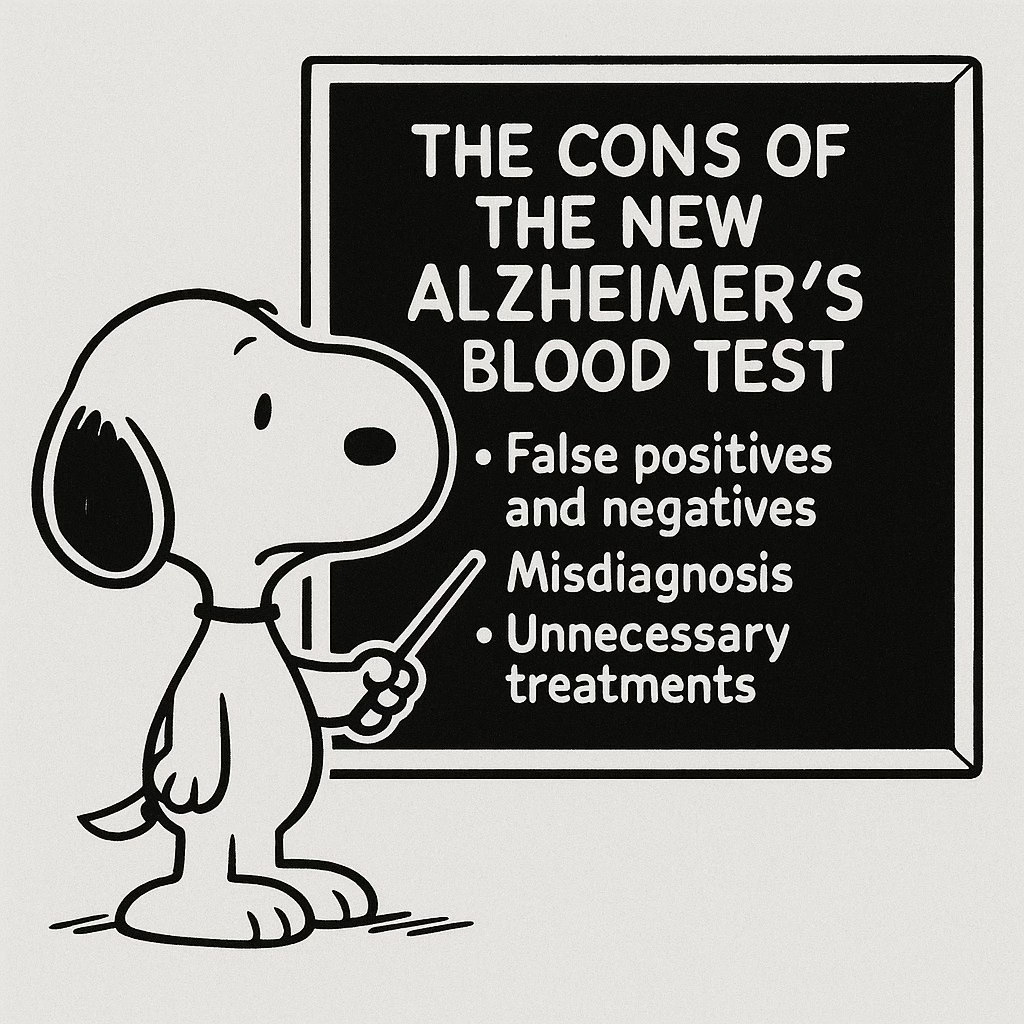

Neurologist Michael Okun, MD, posted caveats on social media, with a graphic, below:

Though this test reflects the new frontier of biomarker-driven neurodegenerative disease diagnosis and and opens the door a little wider for earlier, more precise interventions there is much work to be done. … I say to persons w/ disease, caregivers, and clinicians: stay informed. This test is a powerful new tool, but like any medical innovation, it must be used wisely, ethically, and as part of a comprehensive approach to care. We must – ecce signum* – behold the signs of dementia, and always remain cautious when making decisions on a single blood test.

* Ecce signum is Latin for “behold the sign” or “here is the proof.”

Some stories briefly mentioned false positive or false negative test results, but many failed to capture the entirety of what the FDA outlined in its news release:

False positive results, in conjunction with other clinical information, could lead to an inappropriate diagnosis of, and unnecessary treatment for, Alzheimer’s disease. This could lead to psychological distress, delay in receiving a correct diagnosis as well as expense and the risk for side effects from unnecessary treatment.

False negative results could result in additional unnecessary diagnostic tests and potential delay in effective treatment.

What you’ve seen in this article are examples of little things - a few comments here or there - that potentially become big things if they confuse and mislead readers. There’s already enough confusion about Alzheimer’s disease and many people living with this disease in their families may be misled by some of the little things that could have been so easily corrected.

Good piece. Mission creep is quite common in the press and is difficult for lay readers to recognize this. Anxious patients regularly query me worried that the heartburn medicines I prescribed for them may cause dementia and other maladies, based on misleading reportage. With regard to a test for Alzheimer's disease, assuming a positive result is true, might there be a permanent erosion in one's quality of life knowing that a terrible diagnosis that has no effective treatment is expected?

Thank you for the insightful coverage of this misunderstood technological advance. As a primary care physician who cares for a senior population I will not order this test. I have a concern about the setting in which the test should be performed. In many healthcare markets it is extremely difficult for patients with cognitive impairment to be seen in a specialized setting. Most neurologists and memory care centers will not even see a patient until the primary care clinician has performed a laundry list of specialized blood tests and imaging. Clinical evaluation and acumen be d*mned. What will inevitably happen is that the Lumipulse test will be indiscriminately ordered in primary care settings.