Mistrust in artificial intelligence in health care - 6 items

Here’s another one of my collections of readings on a given topic - today a glimpse of six concerns about mistrust in artificial intelligence in health care and science. My focus is always on things that impact the public dialogue about health care, so I think this trust issue is clearly relevant to my area of concentration.

Questions about the FDA and AI

Feelings of mistrust in the FDA’s management of artificial intelligence issues were reported by STAT News (full story is behind a paywall):

STAT reported:

Food and Drug Administration officials hit a major milestone list year: a running list of medical devices enabled by artificial intelligence eclipsed 1,000.

But in the last nine months, the office focused on AI products has stopped providing updates altogether. So STAT’s Katie Palmer made a list herself: the FDA has authorized at least 167 AI/machine learning devices since the last listed decision in September.

Since taking office, the Trump administration has dismissed (and in some cases, later attempted to re-hire) several of the agency’s AI experts, leaving a potential knowledge vacuum inside an agency already struggling to keep up with the fast-changing AI landscape. And without a clear accounting of its own authorizations, the agency is leaving much of the public in the dark. In the words of one Stanford researcher focused on AI-aided medical devices: “We need more transparency, not less.”

Patient trust in health systems & AI

A research letter in JAMA Network Open reported results of a large national survey that found:

Most respondents reported low trust in their health care system to use AI responsibly (65.8%) and low trust that their health care system would make sure an AI tool would not harm them (57.7%).

The authors concluded:

Low trust in health care systems to use AI indicates a need for improved communication and investments in organizational trustworthiness.

Bias & disparities in AI

The Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) suggested to its members several angles to consider in writing on AI topics. None specifically mentioned trust issues, but all of them pointed to possible disparities and built-in biases in the way AI algorithms are formulated based on the data that are input. This could lead to public mistrust in the AI models and algorithms.

One of the angles referred to this 2022 paper in PLOS Digital Health:

The authors summarized:

Our study demonstrates substantial disparities in the data sources used to develop clinical AI models, representation of specialties, and in authors’ gender, nationality, and expertise. We found that the top 10 databases and author nationalities were affiliated with high income countries (excluding China), and over half of the databases used to train models came from either the U.S. or China. While pathology, neurology, ophthalmology, cardiology, and internal medicine were all similarly represented, radiology was substantially overrepresented, accounting for over 40% of papers published in 2019, perhaps due to facilitated access to image data. Additionally, more than half of the authors contributing to these clinical AI manuscripts had non-clinical backgrounds and were three times more likely to be male than female.

I applaud AHCJ for publishing a piece like this that helps journalists think of story ideas in their communities.

Concerns about AI for mental health support

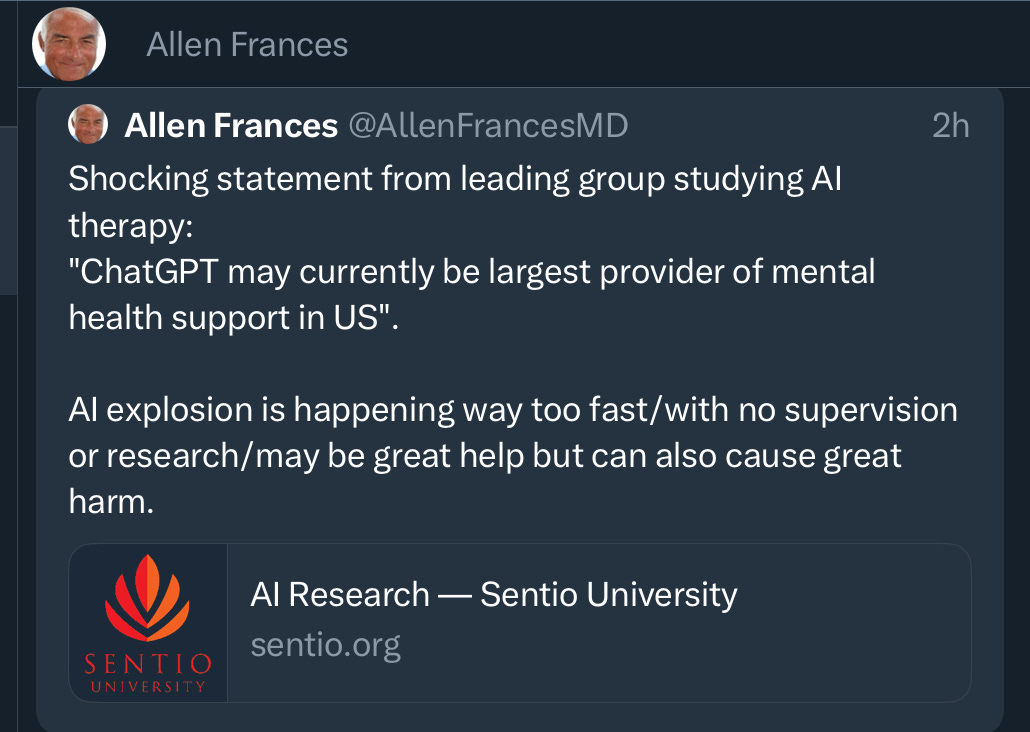

Psychiatrist Allen Frances, MD, Professor and Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University School of Medicine, has been writing and talking quite often about his concerns about AI for mental health support.

He has made some positive observations.

That comment came two years after a 2023 article, in which he listed six limitations of AI for mental health support:

Lack of empathy: AI language models lack true understanding and emotional intelligence. They can generate responses based on patterns in data, but they do not have emotions or the ability to empathize with users in the same way a human therapist can.

Inability to build rapport: Establishing a strong therapeutic alliance and rapport is crucial in psychotherapy. Human therapists can adapt their approach, build trust, and form meaningful connections with their clients, which is a vital aspect of the therapeutic process.

Limited understanding: AI language models might not fully comprehend the nuances of complex emotional and psychological issues. Their responses are based on patterns in data, and they may not be sensitive to the unique circumstances of each individual.

Ethical concerns: Confidentiality and privacy are paramount in psychotherapy. AI systems may raise ethical concerns regarding data security and the potential for sensitive information to be mishandled or misused.

Risk assessment: AI models may struggle to accurately assess the risk of self-harm or harm to others, which is a critical aspect of mental health support.

Legal and regulatory considerations: The use of AI in mental health support raises questions about liability and accountability in case of adverse outcomes.

This past March he warned on social media:

This month he added more concerns.

There is a growing body of literature on AI for mental health support, including this randomized clinical trial:

Emotional risks in AI apps

On a somewhat related topic, a paper in Nature Machine Intelligence entitled, “Unregulated emotional risks of AI wellness apps,” suggests that some wellness apps:

“…can foster extreme emotional attachments and dependencies akin to human relationships — posing risks such as ambiguous loss and dysfunctional dependence — that challenge current regulatory frameworks and necessitate safeguards and informed interventions within these platforms.”

The authors believe that app providers should take steps “to both prevent and mitigate mental health risks stemming from these attachments.”

Negative public perceptions of AI science

Although it did not specifically address AI in health care or biomedical research, a paper published in PNAS Nexus addressed related issues.

The researchers found that people perceived AI scientists more negatively than climate scientists or scientists in general, and that this negativity is driven by concern about AI scientists’ prudence – specifically, the perception that AI science is causing unintended consequences. But rhey found that perceptions of AI are less polarized than perceptions of science and climate science. Part of the researchers’ summary:

The public unease about AI's potential to create unintended consequences invites transparent, well-communicated ongoing assessment of the effectiveness of self or governmental regulation of it. At the same time, it is imperative to examine whether perceptions of AI result, in part, from novelty. New technologies are often met with skepticism and even moral panic and so to reduce novelty bias, our study examines perceptions of AI over time as well.

Some other reading on this topic:

The MAHA children’s health report mis-cited our research. That’s sloppy -— and worrying. (AI connection)

KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll: Artificial Intelligence & Health Information

New Vatican document offers AI guidelines from warfare to health care.

Finding Consensus on Trust in AI in Health Care: Recommendations From a Panel of International Experts (Journal of Medical Internet Research)

Public perceptions of artificial intelligence in healthcare: ethical concerns and opportunities for patient-centered care. (BMC Medical Ethics)

Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: review & recommendations (Japanese Journal of Radiology)

I’ll keep following issues with AI in health care and will post more when the collection warrants attention. Thanks for your interest.