I’ll probably never get around to writing many book reviews on this site. I’m very late in writing this one. But I must add my comments to the many glowing reviews about what I consider to be one of the best books I’ve read in a long time. But it’s also one of the saddest books I’ve ever read.

Although the words aren’t in the book’s title, it’s about medical whistleblowers - people who see something that they believe is wrong and try to bring attention to it and to remedy it. The author, Carl Elliott, is a philosopher who trained in medicine, became a bioethicist, teaches medical ethics, and who found out what can happen when you become a whistleblower.

Elliott blew the whistle on his own institution, the University of Minnesota. He was questioned by local reporters about the suicide of a young man with mental illness. Dan Markingson was enrolled in a psychiatric drug study “over the objections of his mother,” Elliott wrote. “She had desperately tried to get him out of the study, but her pleas were ignored.” When Elliott looked deeper, he found:

The study was marked by alarming red flags, conflicts of interests, financial pressures to get subjects into the study, a locked psychiatric unit where severely ill patients were targeted for recruitment. … Not only was Markingson psychotic when he signed the consent form, he was under a civil commitment order that legally required him to obey the recommendations of his psychiatrist. His mother wanted him to have nothing to do with the study. (He) was enrolled anyway.

Elliott’s involvement became a long, complex story - one that I won’t do justice to here. He found resistance and anger from his university. The case was closed. He was finding no help from state and federal agencies. He felt terribly alone. Many details of the case appear in the Death of Dan Markingson Wikipedia page.

Publicity of the Markingson story resulted in many people approaching Elliott - “psychiatric survivors, patient advocates, would-be whistleblowers, civil libertarians, anti-pharma activists, Scientologists, and conspiracy theorists of every possible variety,” he wrote. He spent years visiting whistleblowers,

trying to understand their stories, comparing each one to the others, attempting to see patterns and draw out common moral threads.

And that became this book. Incredible, shocking, terrible stories that only came to light because of the convictions of people who blew the whistle.

“The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”

That’s what it was called. And that’s what they did. Over 40 years’ time, researchers studied the effects of syphilis when you didn’t treat it. The 400 men studied were offered incentives to participate, but were deceived by the researchers and weren’t even told of their diagnosis. More than 100 died as a result. It’s also the story of a man named Peter Buxton and an AP reporter, Jean Heller, who exposed “the most notorious medical research scandal in American history.”

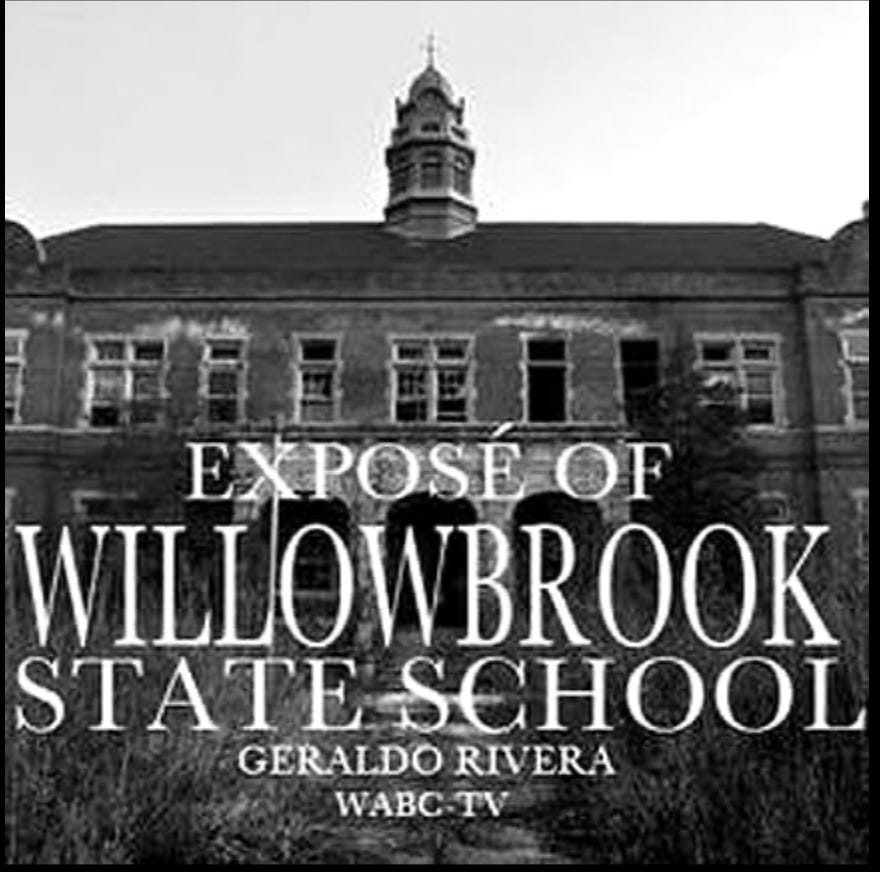

Willowbrook State School for intellectually disabled children

Researchers intentionally infected “mentally defective” children with hepatitis. Elliott wrote:

So crowded and unsanitary was the school that many children contracted hepatitis anyway, research study or not. If hepatitis was virtually inevitable, why should it matter if the children were infected intentionally?

The whistleblower in this case was Mike Wilkins, a physician who worked at Willowbrook in the 1970s. Wilkins worked with Geraldo Rivera, then at WABC-TV in New York, to plan a documentary on the school.

The Hutch - Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

The Seattle Times reported this story under the headline, “Uninformed Consent: What patients at “The Hutch” weren’t told about the experiments in which they died.” It began like this:

For nearly two decades, Dr. John Pesando sounded the alarm over what he saw as a dangerous and unethical human experiment at Seattle's Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

In the 1980s, he complained from the inside: As a member of an oversight committee at "The Hutch," he repeatedly objected to the clinical trial in which leukemia patients were dying at unusually high rates.

In the 1990s, he complained from the outside: In letter after letter - to members of Congress, to federal and state agencies, to newspapers - he said "many good people needlessly lost their lives" in the leukemia experiment, which lasted from 1981 to 1993.

Elliott wrote about Pesando: “His is a bleak, demoralizing story of defeat.” He quotes Pesando saying, “At some point you have to question your values and say, ‘Why am I the only person in the room who thinks this way?’ “

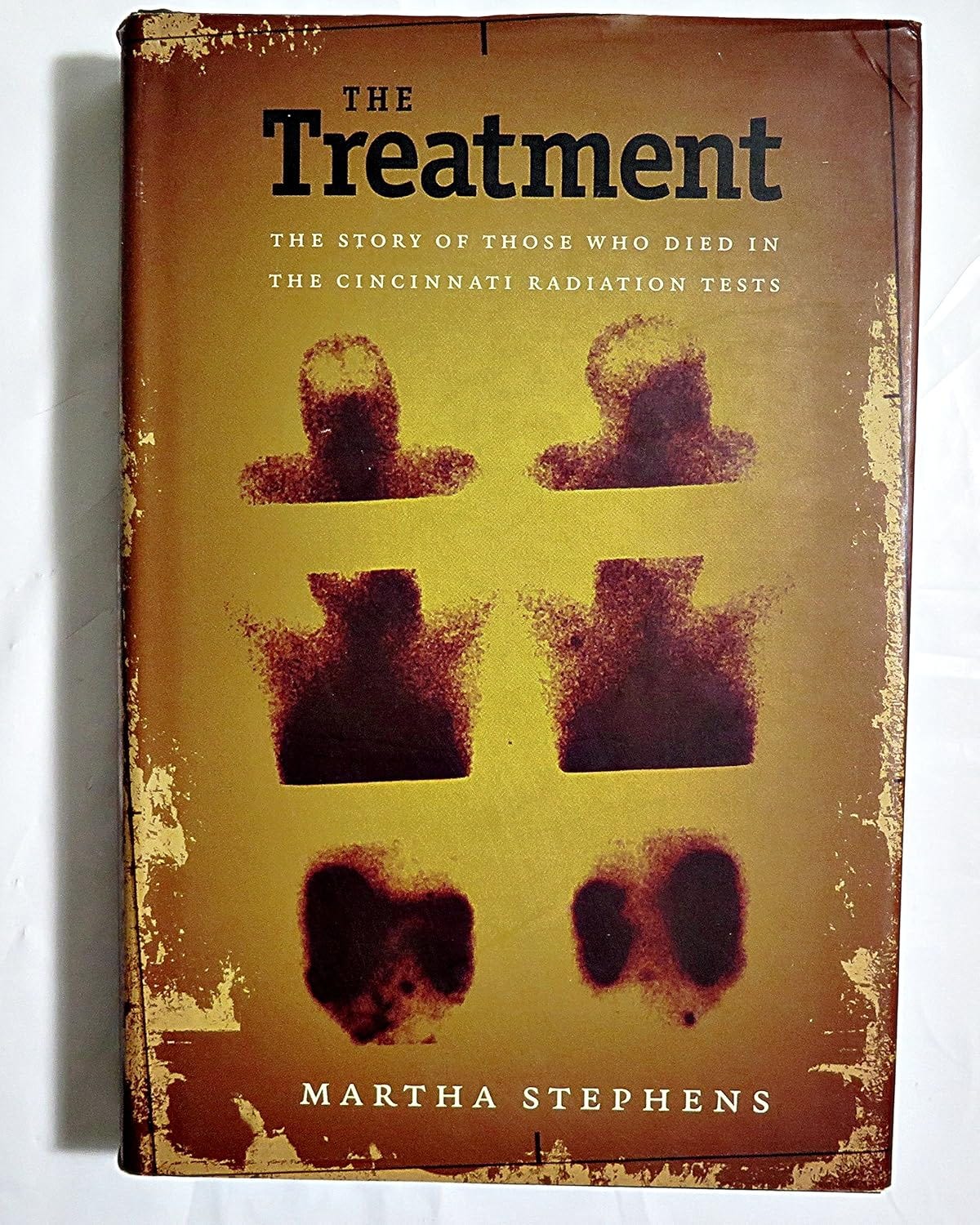

The Cincinnati Radiation Experiments

The lead whistleblower in this case was Martha Stephens, a young assistant professor in the English department at the University of Cincinnati, whom Elliott describes as “the rare bird who blew the whistle twice” - once in 1972 and then 21 years later after a newspaper story looked into secret Cold War radiation experimentation, including that at the U of C.

The experiments were to study how soldiers in nuclear warfare might react after being exposed to long-term doses of lots of radiation. She dug up details that showed at least 90 people between 1960-72 were radiated - at doses comparable to 20,000 chest x-rays within hours. Nearly a quarter of subjects died within 38 days of being radiated. Others had nausea, vomiting, and cognitive impairment. No written consent forms were used during the first five years of study. Subjects were misled, told that the study was to help with their cancer. The majority of subjects were working class Blacks.

It was a long, ugly fight for Stephens and those who tried to help. She wrote a junior faculty report, worked with journalists, and wrote a book. Finally, in 1999, a lawsuit was settled for over five million dollars paid by the university, the city and the individual researchers. Most families got about $50,000.

The New Zealand “Unfortunate Experiment”

The scandal here was that women with a precursor of cervical cancer were deceived and left untreated for decades. Many of them died. An ob-gyn named Ron Jones, along with several physician colleagues, helped expose the scandal, calling it “the unfortunate experiment.” Once again, journalists helped the cause. Jones and colleagues tried for years to stop the experiment but the public didn’t learn about it until a magazine published a story based on an article the physicians had published in a journal.

Elliott wrote that “It is one of the rare scandals where some measure of justice was eventually achieved. The victims were given a public forum and the architect of the study was forced to answer for it.” But Jones seemed haunted when he spoke to Elliott, saying:

It’s never out of my mind. There’s not an hour of the day when some aspect of it raises its head in my life. And this is forty years later. I cannot escape it.

I am quite sure that same feeling lives within Elliott as well.

The Karolinska Institute’s artificial trachea transplant experiments

“A milestone in medicine,” CNN called it in 2008 after surgeon Paolo Macchiarini performed one type of novel trachea repair. Soon the surgeon was invited to join the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. He began implanting the world’s first artificial trachea into patients. But questions arose about his methods and about how many of his patients were dying.

Meantime, NBC aired a 2014 documentary, A Leap of Faith, that compared the surgeon’s accomplishments to Neil Armstrong’s moon walk. Then a 2016 documentary, The Experiments, on Swedish television, led to the surgeon’s dismissal. Elliott wrote:

In the years since The Experiments aired, Macchiarini has been exposed as a medical con man unlike any other; a fabulist, a fraud, a globe-trotting Casanova who lied to women as smoothly as he did to his patients. Macchiarini concocted a false biography and published fraudulent scientific papers; he manipulated the press like a public relations professional. All this he did with such facility that he fooled experts at the highest levels of academic medicine.

Elliott wrote that the 2016 The Experiments documentary ended it all - “rarely has a work of investigative reporting on a medical research scandal produced such devastating consequences.”

Wikipedia posted that a Swedish news agency reported that in 2020 Macchiarini was convicted of causing bodily harm to several patients who had "serious physical injuries and great suffering" as a result of the operations performed on them. In 2023 his sentence was increased to two years and six months imprisonment after being found guilty of gross assault against three of his patients by an appeals court in Stockholm.

Four physicians blew the whistle: Matthias Corbascio, Kalle Grinnemo, Thomas Fux and Oscar Simonson. Elliott writes that retaliation against them came quickly. The Karolinska Institute reported them to the police. Karolinska officials still supported Macchiarini. The Lancet applauded that decision. Elliott writes in detail about how their lives have been affected.

Overriding themes

Elliott writes that books about whistleblowers usually end with “a tribute to their bravery, an affirmation of their necessity, and perhaps a call to arms.” But, he warns:

Anyone weighing a decision whether to blow the whistle on abuses to human research subjects needs to understand that whistleblowing is a poor mechanism for institutional reform, and only so much can be done to protect those who speak out. … Even whistleblowers who are not fired or demoted often come away from their experiences deeply scarred, often for reasons they struggle to articulate. …Some whistleblowers walk away from the wreckage unhurt. But nobody should indulge in the fantasy that they will be celebrated for blowing the whistle. It is more likely they will be vilified, forgotten, or both.

“Man has a horror of aloneness,” Elliott quotes Honoré de Balzac. “And of all kinds of aloneness, moral aloneness is the most terrible kind.”

That sense of moral aloneness hangs over this book like a dark cloud. I can feel it in Elliott’s self-reflection, which he shares openly. And it pours out of each of the whistleblowers’ stories from chapter to chapter.

“Yet, if the effort to expose wrongdoing is seen as a matter of honor,” he concludes, “then success is measured not in material accomplishment but in the achievement of self-respect.”

Final thoughts

I can’t do justice to this book even with this long post. I hope that I inspired you to read it yourself. It must have been a terribly difficult book to research and write. The cases described are painful to review, but I had a difficult time putting the book down after exhaling deeply at the conclusion of each chapter.

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. My grandchildren and I thank you.

I agree Gary. Carl's book is fabulous, but also deeply depressing. Given the enormous toll that whistleblowing involves, I now understand why so people do it.

Thank you. It sounds grim. With current events I’m not sure I can stomach more awful news. Every day seems to bring a new overnight revelation. But knowing there are people willing to speak out does restore some faith.