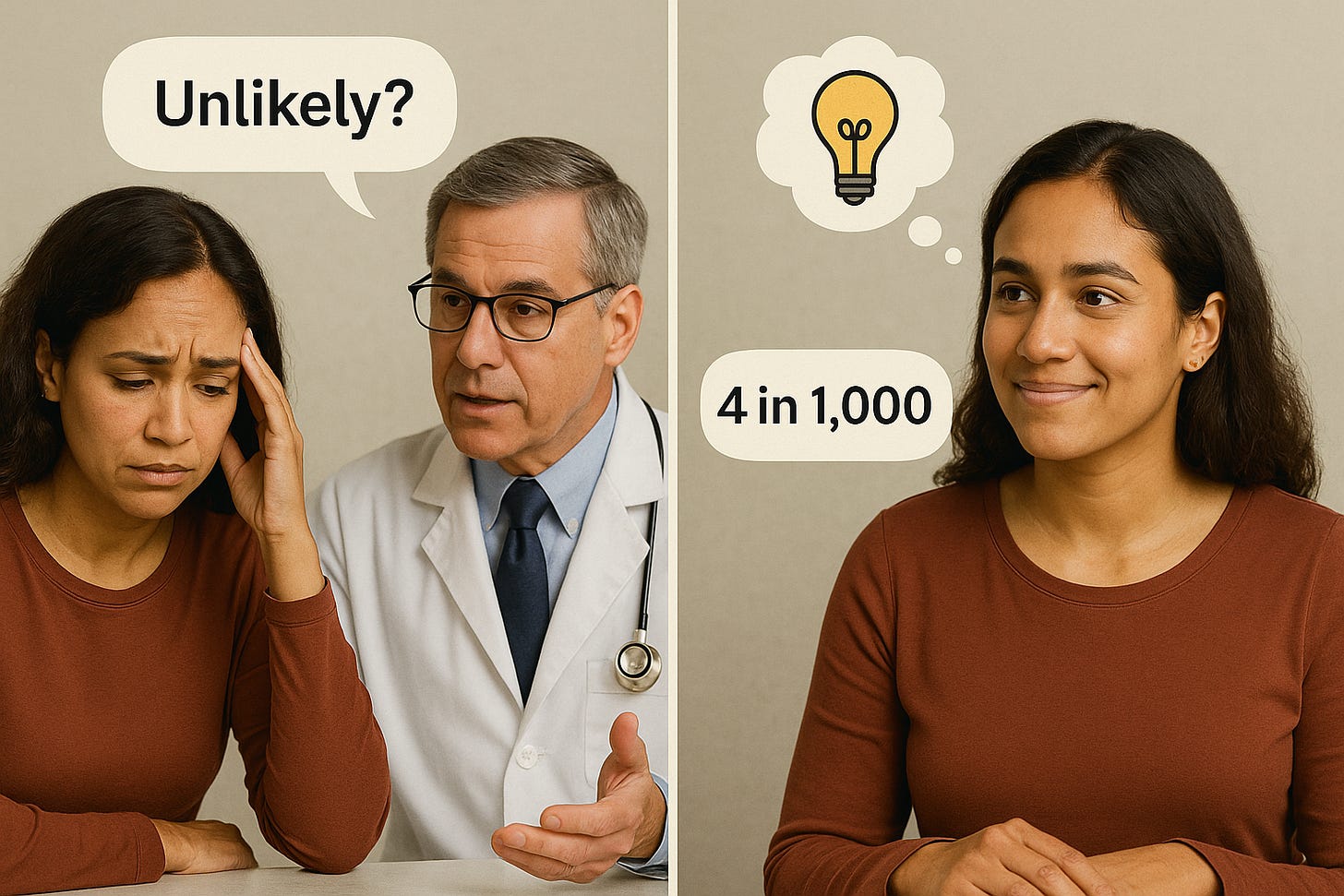

How numbers help patients more than vague terms

Lessons for physicians, patients and journalists or whoever writes about health care

An important paper - “How to communicate medical numbers” - was published in a recent edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). This is so important - for the doctor-patient relationship, for what journalists write for the public, and for individual decision-making.

One of the authors, Angie Fagerlin, PhD, of the University of Utah medical school and Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, was interviewed for a JAMA podcast. She said the article was written in the context of trying to help patients make better informed decisions.

For example, in breast cancer or prostate cancer, one of the things that I’ve heard from patients in those areas - they’ll say, “The most important thing to me is to increase my likelihood of survival.” But then, when we look at the decisions that they make, we’re seeing that they’re making decisions that are actually decreasing their likelihood of survival. The treatments that they actually chose, actually were the treatments that were most likely to lead to an earlier death. Or they might say, “The most important thing is to avoid erectile dysfunction.” And then they chose the treatment that had the highest likelihood of erectile dysfunction. In those cases, I think what one of the problems was they didn’t understand the numbers.

Using numbers could help in many situations. But the authors are aware of the challenges, because the “effectiveness of sharing numerical information depends on patients’ ability to understand and interpret these numbers.” They cite data that showed only 34% of 4,637 US adults were able to perform simple numerical tasks (eg, identify the largest value in an unordered list). Further, 97% of adults at the lowest numeracy level had the lowest literacy, and 81% had not completed high school.

The paper’s conclusion was:

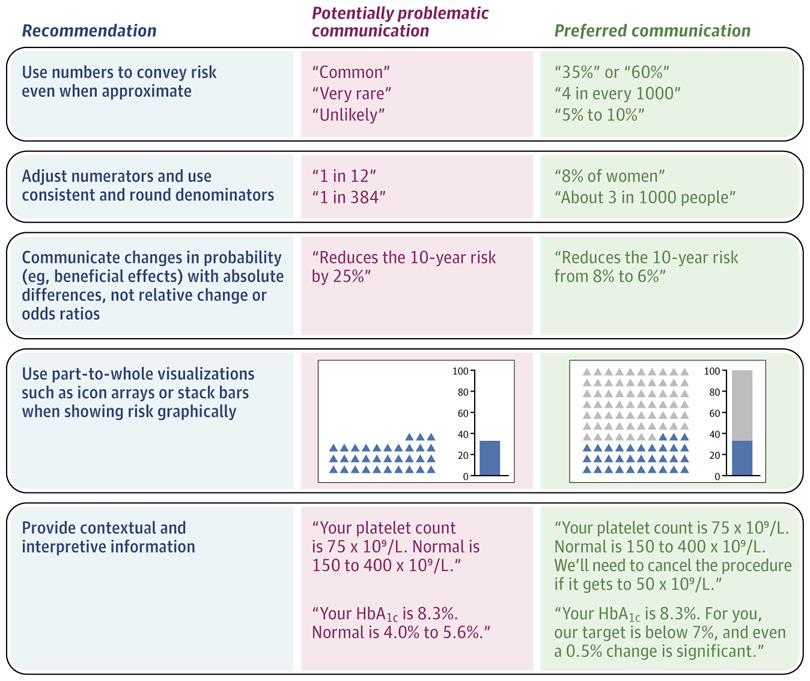

When communicating health numbers to patients, clinicians can improve patient understanding by presenting information using numbers rather than providing verbal probability terms such as rare, common, or unlikely; using consistent denominators; discussing absolute rather than relative risks *; and providing context for unfamiliar types of data.

(* hyperlink to archived toolkit article on absolute vs. relative risk from my former HealthNewsReview.org website)

Examples were provided with this graphic:

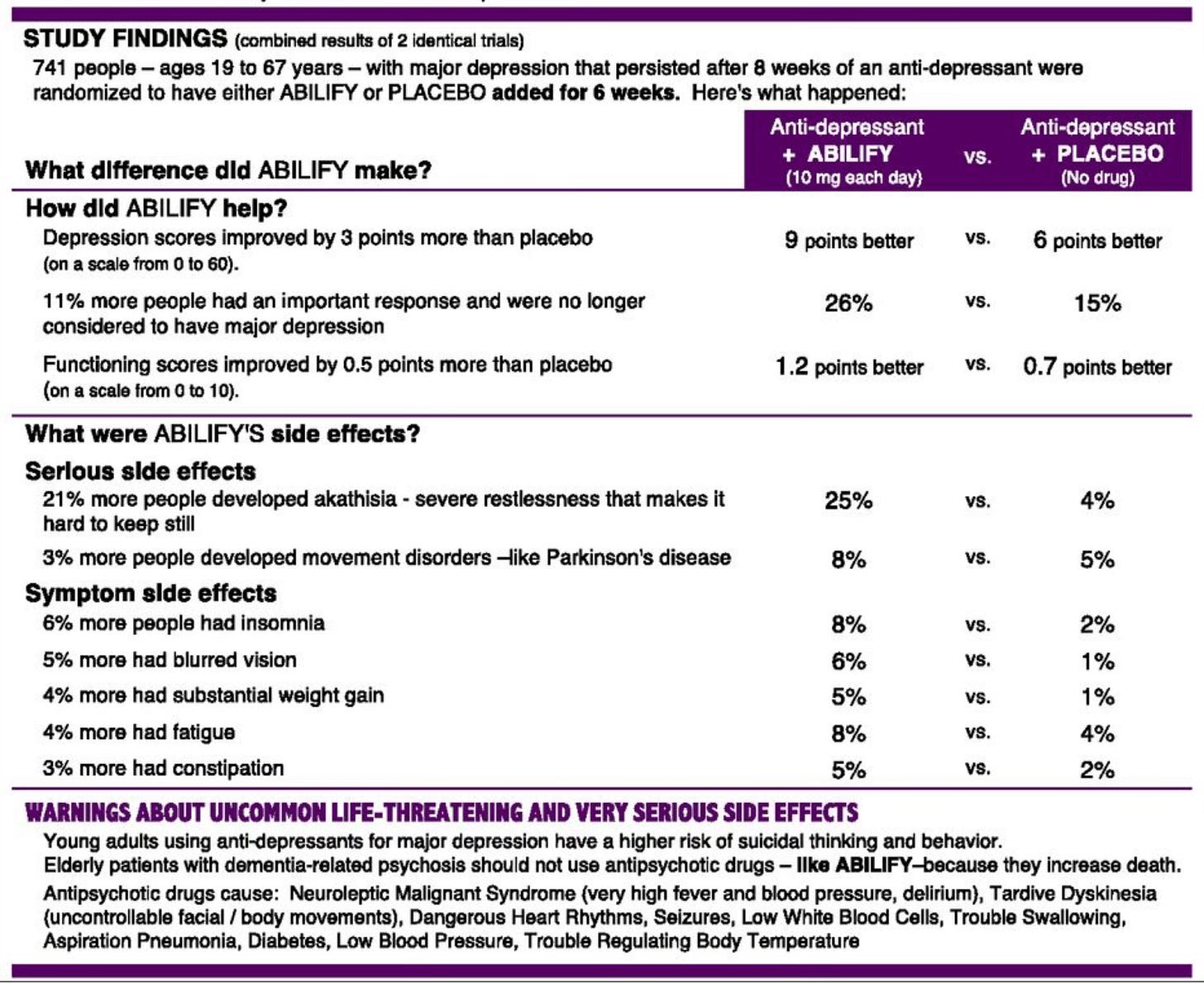

Past work by other researchers is worth noting. For years, Woloshin and Schwartz promoted drug fact boxes to the FDA, to journalists and to the general public. Here’s one example, depicting the trade-offs involved in the Abilify (aripiprazole) drug for depression.

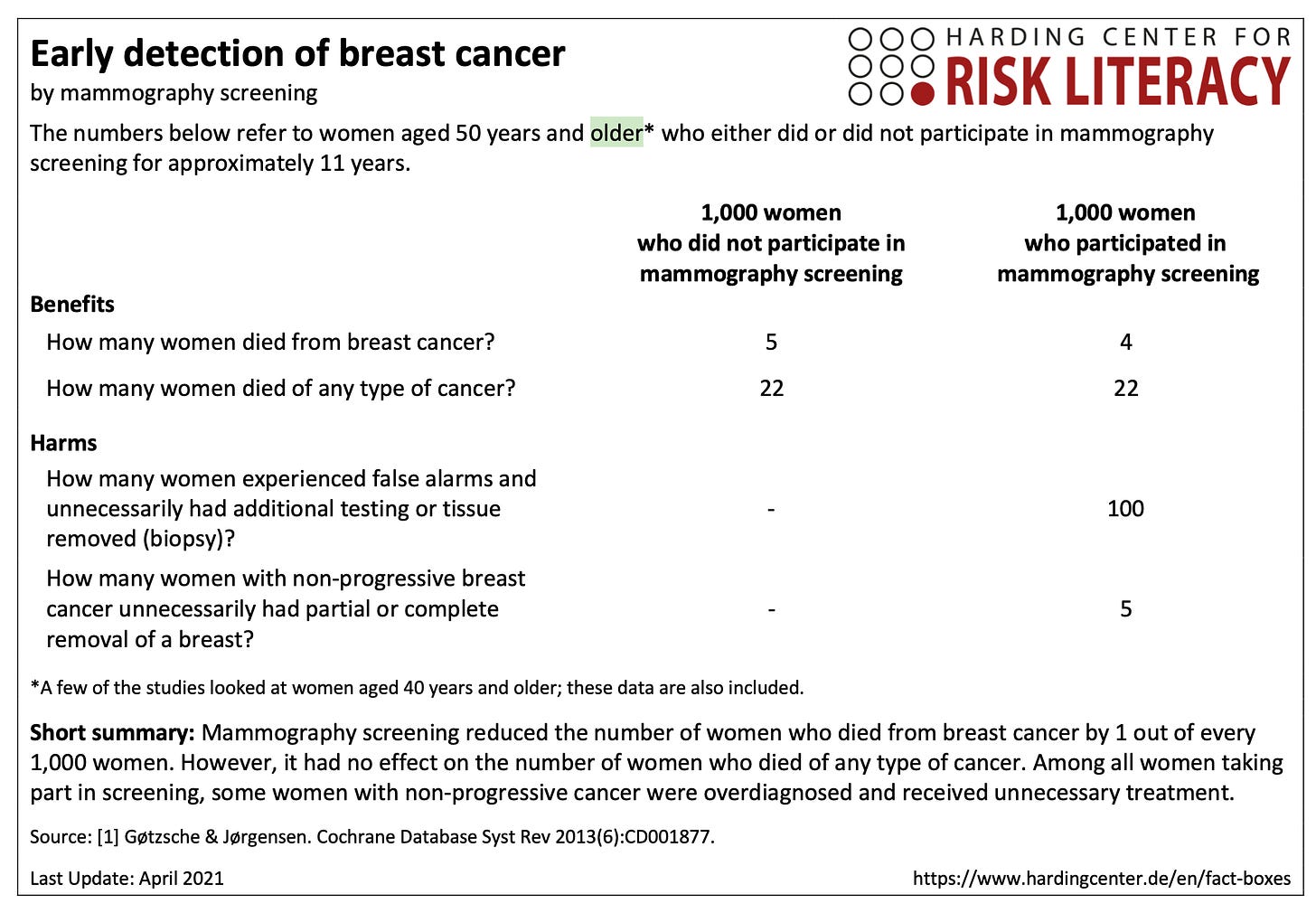

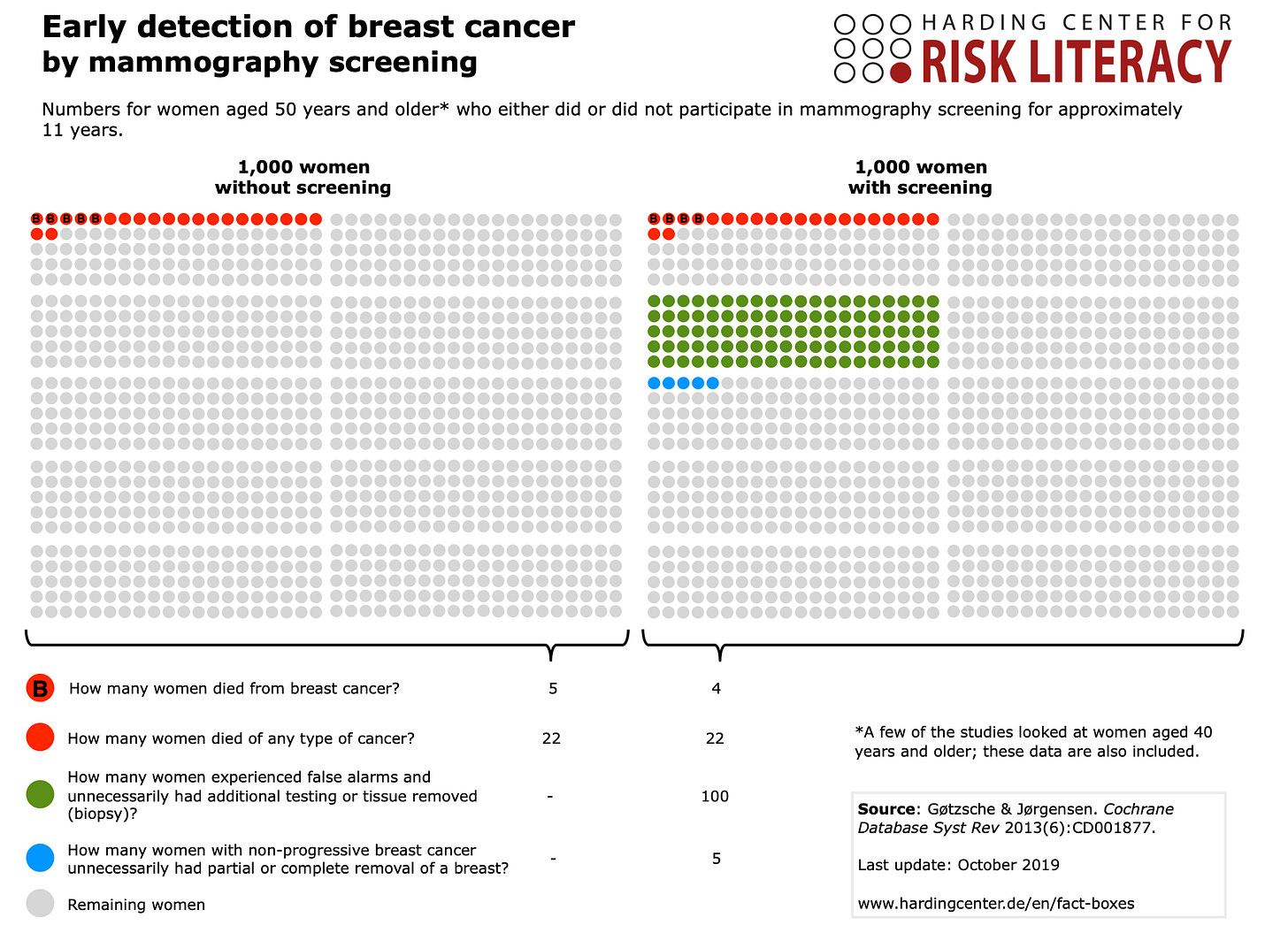

Here are two mammography screening examples from the Harding Center for Risk Literacy at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin.

Journalists should learn how to use such fact-boxes in their stories. More physicians should explore such tools for use with patients. And patients could ask for probabilities to be communicated more clearly with words and numbers and graphics as shown in this article.

This really sheds light on Abilify and mammography. Are any actual clinicians using this approach on the ground? I've never seen it in the wild. Then again I've tried to explain potential harms of screening to patients and it's quite difficult.