Disease-mongering in pharma obesity event

Why wait for disease when you can medicate healthy people now?

Way back in 1992, science writer Lynn Payer introduced the term “disease mongering” as she published a book about the concept. She defined disease-mongering as the "selling of sickness that widens the boundaries of treatable illness in order to expand markets for those who sell and deliver treatments". Exaggerating the seriousness or prevalence of a condition, medicalizing life itself, and turning healthy people into sick ones - these are all elements of disease-mongering.

33 years later, we see new examples all the time.

One of them jumped off the screen as I watched this online event on what was proclaimed World Obesity Day on March 4.

First, there is an ethical problem with a leading Canadian newspaper - The Globe and Mail of Toronto - partnering with a drug company sponsor - Novo Nordisk - to present a 2.5-hour online event about the hot products in the company’s pipeline - its GLP-1 agonist drugs. Some of the drugs in this family have been approved for use in people with excess weight and others have been OK’d for use in people with Type 2 diabetes.

The Statement of Principles of the Association of Health Care Journalists (the first version of which I wrote in 2004), states:

We should strive to be independent from the agendas and timetables of journals, advocates, industry and government agencies. … We are the eyes and ears of our audiences/readers; we must not be mere mouthpieces for industry, government agencies, researchers or health care providers. …

We must preserve a dispassionate relationship with sources, avoiding conflicts of interest, real or perceived.

I see this event as more “mouthpiece for industry” than “independence from the agendas of industry.” I don’t see a newspaper - drug company partnership in an event as “a dispassionate relationship.”

Several of the physicians who spoke during the Novo Nordisk-sponsored event have financial ties - grant funding, consultant fees, etc. - with Novo Nordisk.

One of them, Ravi Retnakaran, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, made some of the comments that jumped out at me. I transcribed one long portion of his presentation about GLP-1 drugs. I have highlighted the portions that stood out to me:

“What’s interesting now is the idea that you have people using these medications to lower weight at an earlier point in the natural history than perhaps may have been done before. And so if you take the transition from having normal glucose to pre-diabetes to diabetes…but now if they would be taking a GLP-1 agonist at a point in time when they have pre-diabetes, we already have evidence for the fact that, yes, you are going to reduce their risk of progressing to diabetes by virtue of the fact that you’re treating them with a GLP-1 agonist. Well, we can take that even earlier. We can think of people with normal glucose levels; diabetes isn’t even on the radar for them. Everything’s normal; everything looks good. But, say they’re taking a GLP-1 agonist to lose weight. Well, you can imagine that you are now going to have a scenario where you are now lessening the challenge that’s going to be posed to their beta cells - that had it been left unchecked was ultimately going to lead to them developing pre-diabetes and/or diabetes. . …But let’s say now that you treated excess weight at an early point in the natural history - let’s say when you’re 30. And you have now changed the anticipated slope of deterioration of your beta cell function such that it may well be that you’re never going to reach diabetes because the challenge being posed isn’t going to happen. And we can extend this thinking to other conditions as well.”

Moderator Andre Picard (a journalist with The Globe and Mail) asked:

“But do you worry about medicalizing people who otherwise feel fine?”

Retnakaran: “I actually don’t and the reason is because I would look at it as we can’t have it both ways. We can’t be saying that this is a chronic condition yet we don’t want to treat it lest we medicalize it.”

“This is an excellent example of disease-mongering.”

That’s what Adriane Fugh-Berman, MD, wrote to me when I asked her to review the excerpt above. She’s a professor of pharmacology and physiology at Georgetown University Medical Center, where she directs the longstanding PharmedOut project. She had more to say:

You can't treat obesity like it's some cancer that if you catch early won't kill you. No one for whom "Everything’s normal; everything looks good" should be treated. There are healthy fat people and unhealthy thin people, and a healthy fat person should be left alone.

Pre-diabetes is a non-condition invented by drug companies to make normal people think they are sick. Most people with this non-condition will never develop diabetes. We are all pre-diabetes. We are also pre-cancer, pre-cardiovascular disease, and pre-death.

Why worry about the lack of evidence?

Since this was a Canadian event, I turned to two Canadians who have studied and written about this topic for reactions to what Dr. Retnakaran said.

Joel Lexchin, MD, is a Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and Professor Emeritus in the School of Health Policy and Management at York University in Toronto. He wrote to me:

"If we listen to what Dr. Retnakaran is saying, then logically we should start giving babies multipills as soon as they are born to ward off all the diseases that they might get later in life. Why worry about the lack of evidence that these pills will actually help them? It’s just common sense.”

Dr. Lexchin recently co-authored an article in the Canadian Family Physician journal entitled, “Weight normatively in action: semaglutide and obesity.” (Semaglutide is the generic name for one of the GLP-1 agonists.) Excerpts:

There is increasing demand for semaglutide in Canada even though there are still outstanding questions about its safety, long-term effectiveness, and the degree to which it reduces outcomes associated with obesity. …

…The European Medicines Agency’s risk management plan for semaglutide highlights potential harmful effects for which there is suggestive evidence, but uncertainty about causation, and includes diabetic retinopathy complications, pancreatic cancer, and medullary thyroid cancer. Effects on pregnancy and lactation and on patients with severe hepatic (liver) impairment also remain unknown.

He points out that in the SELECT trial (Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People with Overweight or Obesity), twice as many patients discontinued semaglutide because of adverse events compared with placebo (16.6% vs 8.2%).

Those are the stories that usually don’t get told at pharma-sponsored events.

No long-term safety data? No problem.

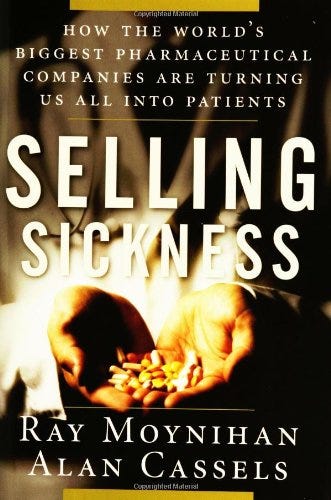

Alan Cassels of British Columbia is an independent drug policy researcher, a writer, and co-author of this 2005 book that built on the disease-mongering theme. His reaction appears below.

“Why wait for disease when you can medicate healthy people now?

Dr. Retnakaran’s pitch for drugging “pre-obesity” with GLP-1 agonists takes disease-mongering to new heights — treating normal weight and glucose levels as ticking time bombs. No long-term safety data? No problem. Just start younger, keep going forever, and call it prevention.20 years ago when my book “Selling Sickness” was published, there was no chapter on obesity. Today this stuff writes itself, which is to say we have sold sickness so often, so deceptively and so utterly convincingly, that hardly anybody blinks when it's happening In stark, raving daylight!”

I want to revisit two other things Dr. Retnakaran said.

1. “And we can extend this thinking to other conditions as well.”

That line fits the 33-year old definition of disease-mongering: widening the boundaries of treatable disease.

2. “We can’t be saying that this is a chronic condition yet we don’t want to treat it lest we medicalize it.”

Actually, yes, you can say that. There are harms from medicalizing conditions in people for whom “everything’s normal and everything looks good.” And there are huge costs and significant potential harms from the use of these drugs that cannot be overlooked.

And you thought drug ads were banned in Canada?

Well, they are generally prohibited - BUT drug companies may run so-called “reminder ads” that may name the drug without mentioning what it’s for. These become the often seen and heard “Ask Your Doctor” ads. Here’s one that greets travelers at the Montreal airport.

The blogTO.com website tried to capture the omnipresence of Ozempic ads in Toronto, with big digital ads seen behind home plate at Blue Jays games….

…and what some have called “a streetcar named Ozempic.”

The Novo Nordisk semaglutide drug Ozempic is not approved as a weight loss treatment in Canada. But that company’s Wegovy semaglutide drug is approved for use in obesity.

Maybe Don’t “Just Ask”

These are complicated issues that shouldn’t be oversimplified in messages to the public, with imagined scenarios for future expanded drug uses. The “Ask Your Doctor” campaign may result in a new campaign backlash, as in the headline of this McGill Science Undergraduate Research Journal piece - Maybe Don’t “Just Ask.”